Advice to Students Entering Research

A prospective student recently asked what I look for in a research student. Some frequently given criteria are “smart” or “hard-working” or “good grades.” That’s fair, but these are not really the factors that are holding back most students (once you get to an adequate level that you probably are at if you’re reading this). This post is an attempt to articulate what factors I believe are important. I thought I should post it publicly in case it’s useful for other students or researchers.

Take “hard-working” for example. In my experience, before trying to work very much more than 40 hours per week on a sustained basis (some temporary increases are allowable), you should make sure that what you are doing is the optimal use of time. You should also track your time to see where it’s actually going and think about whether it matches your priorities. Time tracking can be really simple, like checkmarks on paper, or it can be more complicated/powerful dedicated software.

Probably the best advice I can give is: find a problem that you’re interested in and get low-key obsessed with it. When I started college, I started training to become an operator for our nuclear reactor. I saw the Inhour equation, and said, “I know Euler’s method. I’ll write a reactor simulator.” And then I saw that that didn’t give a reactor that handled as real reactors do, so I wrote down the point kinetics equations. And then I saw that Euler’s method worked, but wasn’t very good for solving those, so I think I must’ve come up with some kind of higher-order solution (this was Freshman year, so I don’t think I had come across something like that in class). The key isn’t that I was the smartest student (I wasn’t) or the hardest working (I wasn’t), but I still did something that no one else did just by finding a problem that I was really interested in and trying to explore it. So having that kind of curiosity about a problem is the most important quality. If you see something that interests you, you should explore it.

Real Tradeoffs

There are some qualities (general intelligence, emotional maturity) that do not really involve tradeoffs. For most qualities, there are tradeoffs, and managing those tradeoffs is the real challenge. I continue to struggle with these challenges myself.

Persistence vs. Sunk cost

The ability to work towards a goal is a good thing. But there’s also the “sunk-cost fallacy,” where people persist in working toward goals that made sense when they started, but now no longer do. So continuing to work can go from being a good quality to being a waste of time. Knowing when to pivot is just as important as knowing how to persist.

Reading/Listening vs. Writing

The literature is large and rapidly expanding. When you’re new, you’ll spend a lot of time reading (stretching from classics of the field to recent work in your area). As you progress, you’ll spend more time doing your own (new) work, but still need to keep an eye on the field (e.g., skimming arXiv listings daily) to find relevant developments. Keeping an eye out also includes going to talks and conferences. The tradeoff becomes especially difficult to manage when you start noticing that developments in other fields are also interesting! For example, I learned about Stan and Hamiltonian Monte Carlo from reading Andrew Gelman’s blog (https://statmodeling.stat.columbia.edu).

Planning vs. Iteration

Another interesting trade is between careful, multiple-year plans, and rapid, iterative development (e.g., Scrum). (You should read the book “Scrum: The Art of Doing Twice the Work in Half the Time” for details or there are lots of summaries online.) Generally speaking, I highly favor Scrum but there are circumstances in which long-term planning and staying with that plan are important (for example, if that workflow is imposed on you by an external organization.) Generally speaking, it is better to rapidly iterate and get feedback than to be more accurate. (We frequently don’t reward that in school with, e.g., one-try exams, but it’s true in research.)

One of the most important skills to develop for iterative development (that we don’t teach much until graduate school unfortunately) is order-of-magnitude physics. This lets you quickly evaluate many possible paths forward to find the most promising one(s) and determine what the requirements for success will be. A recent example of this I enjoyed is “Direct High-Resolution Imaging of Earth-Like Exoplanets” by Slava Turyshev (https://arxiv.org/abs/2506.20236). I recommend getting extremely good at this style of reasoning.

Focus vs. Opportunity

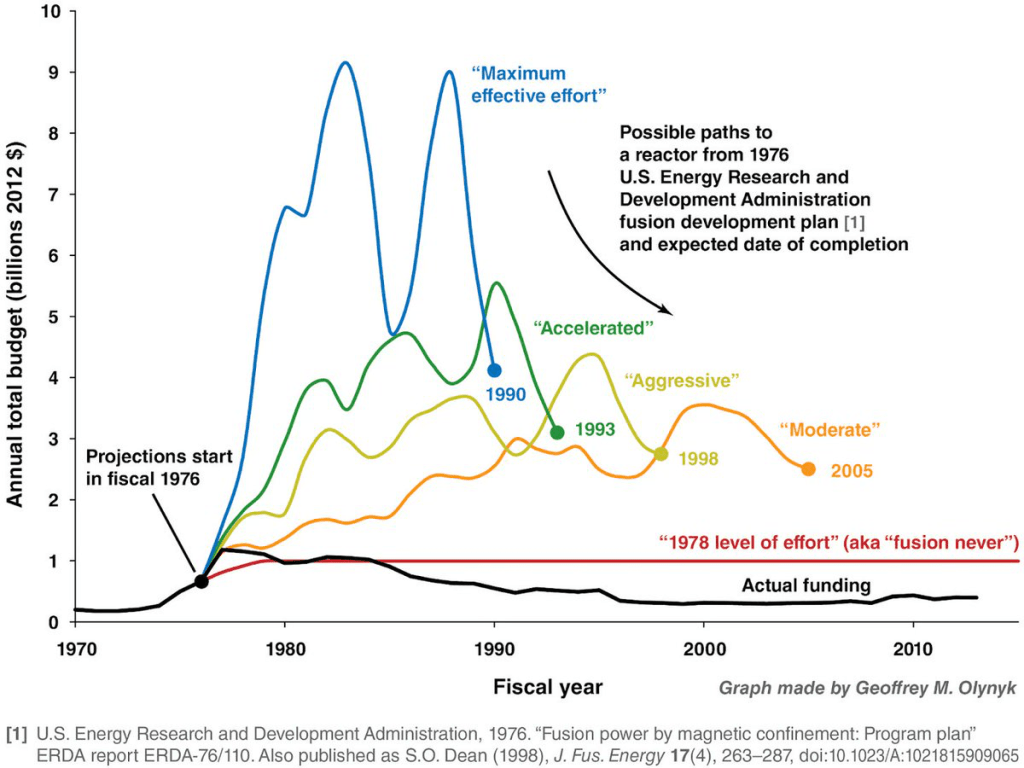

Another example is that it’s good to take promising opportunities when you see them. However, this can result in overcommitment, thus spreading yourself too thin. Now, you may think, “Well, I’ll continue to work steadily towards all of my goals.” But this can lead to a phenomenon I refer to with this chart. This chart shows different projected funding scenarios for when fusion power might have been achieved as starting from 1976. (I’m not sure about the exact data being plotted, so take the graph seriously but not literally.) You’ll note that one scenario never achieves fusion and is thus labeled “fusion never,” even though consistent effort is being put into developing fusion reactors. The takeaway is that steady effort isn’t enough, without a sufficient level of focus, constant progress may not succeed.

Efficiency vs. Innovation

Another tradeoff is that when you find a promising technique or promising data source, you are tempted to work there until you get all the value from it. This is efficient, but it also makes you vulnerable to “disruption,” where new techniques/data sources/organizations can come along and accomplish the goal better. So you should extract value, but you should also look to self disrupt. For example, SpaceX has the most successful rocket family on the planet (Falcon) and the most successful crew spacecraft (Dragon), but they are working very hard to disrupt them with Starship. In 2010, Apple was building the best laptops, but they recognized that these machines were overkill for some users who wanted basic functionality. So Apple disrupted the MacBook by introducing the iPad.

A Tradeoff for the 2020’s: Doing it Yourself vs. with a Large Language Model

You should experiment with Large Language Models like ChatGPT to get a sense of what they can do and can’t do. I would advise being very careful about using LLMs for writing (the hardest part of writing is thinking, and this is something you should do yourself to get and stay good at it). However, LLMs are wonderful for looking up code options and errors (my Stack Overflow usage has definitely dropped off), acting as a sounding board for questions and thoughts, and even writing simple functions. As LLMs get more functional, this tradeoff will become even more difficult to manage.

Summary

So, what makes a good researcher? Someone who is curious, intentional about how they spend their time, and aware of the need to manage the many tradeoffs that research entails.

Appendix: False Tradeoffs

There are also tradeoffs that researchers think exist, but really do not. Here’s a few of them:

*Staying quiet versus admitting you do not know something. Just ask; most of us are friendly!

*Avoiding a meeting versus admitting that you did not make as much progress as you hoped. Meetings/check-ins are part of rapid iteration. It may turn out that your project needs a re-plan or adjustment, and avoiding meetings just delays that process. I almost never make as much progress as I’d like!

*Avoiding getting feedback versus having it be perfect when you present it. This is just a variant of the above. Ask for feedback early and often!